If you were asked to provide a list of Black icons of civil rights, social justice, and activism, what figures would you name? It’s very likely that several mainstays of those categories would come up: Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, Angela Davis, etc. Maybe you’d stray slightly off the beaten path and opt for Fannie Lou Hamer, Julian Bond, or Ida B. Wells, but odds are that you’d mention at least one of the names listed.

Naturally, certain figures of any observable category can be elevated beyond others in that category. Sometimes this is a result of the magnitude of those figures’ accomplishments or contributions, and other times political or social concerns are responsible. In the category of Black activism, the names that get mentioned most are the names that are typically regarded as having done the most to improve the quality of Black life. Dr. King and Malcolm X are often considered the two foremost personalities of the Civil Rights Movement, and the Civil Rights Movement is often considered the foremost effort made in the interest of Black activism, so their names are forever imprinted on the plaque of Black history.

As impressive as the accomplishments of the most noted civil rights giants are, their status as household names doesn’t suggest that they’re also the most important names. Countless Black activists before and after those who come up most in conversation worked just as hard—if not harder—to vanquish racism, further Black interests, and improve the quality of Black life. Here are three lesser-known icons of activism to look into this Black History Month:

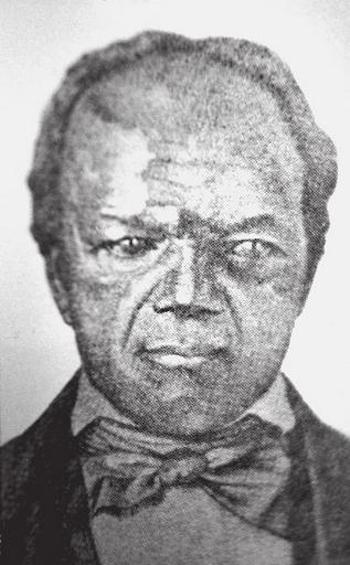

John Berry Meachum

John Berry Meachum (1789-1854) was, in a word, unstoppable. The many roadblocks faced by Black Americans before the Civil War

were meaningless to him and his mission to uplift the race in any way he could. Born a slave, Meachum began his march toward justice by becoming skilled enough in carpentry to monetize it and purchase his own freedom at the age of twenty-one, and later, his father’s, mother’s, siblings, and his wife’s freedom. After freeing his parents, Meachum was propositioned by his former owner to lead his seventy-five remaining slaves from Kentucky to the free soil of Indiana, which he did. If Meachum is beginning to sound a bit like Harriet Tubman to you, you may appreciate knowing that Meachum and his wife Mary also worked as conductors on the Underground Railroad.

In order to purchase his wife’s freedom, Meachum had to travel to where she’d been sold in St. Louis, Missouri. The two remained in St. Louis while Meachum sustained them and their children by working as a cooper, or barrel maker. He later met John Mason Peck and James Welch, two Baptist missionaries. Meachum helped them establish a Sunday School for Black churchgoers that disrespected Missouri laws against educating Blacks. After being ordained as a minister by Peck, Meachum built and founded his own church, the First African Baptist Church, which was the first Black church west of the Mississippi River.

Meachum continued to educate free and enslaved Blacks through the church but hit a snag in 1847 when laws against Black education became considerably stricter. Meachum was arrested and the school was shut down. After being released, the undeterred Meachum bought a steamboat to teach classes on in the Mississippi River, as the river was not under Missouri’s jurisdiction. Meachum’s “Floating Freedom School” appropriately became a famous symbol of Black ingenuity and resistance. One of Meachum’s students was James Milton Turner, who opened 30 schools for educating Blacks and founded the Lincoln Institute (now Lincoln University), the first Black institution for higher learning in Missouri.

Claudette Colvin

Nine months before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white person on a bus, Claudette Colvin (1939—), a fifteen-year-old girl from Parks’ own Montgomery, Alabama, did the exact same thing. After being importuned by the bus driver to get up, Colvin cited her constitutional rights and refused to leave her seat. She was promptly removed and arrested to a chorus of jeers by the bus’s white

patrons.

Colvin’s story and arrest piqued the interest of the NAACP’s Montgomery chapter, which raised money and support to appeal her convictions. Following Rosa Park’s similar defiance and the subsequent Montgomery bus boycott, Colvin served as one of four plaintiffs in the 1956 case of Browder v. Gayle, which began when the attorney from her initial court appearance, Fred Gray, filed a lawsuit to challenge bus segregation in Montgomery. The district court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional, a decision that was then affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Today, Colvin’s actions and the movement they helped incite have cemented her as an undeniable—albeit woefully underpraised—pioneer of the Civil Rights Movement.

Hazel Scott

Hazel Scott (1920-1981) was as talented as they come. A musical prodigy, she received a scholarship to study at the Juilliard School when she was only eight years old. Scott played piano professionally while still in school, and quickly expanded her repertoire when she began as a jazz singer. Her talents also led to multiple appearances as an actress on Broadway and in Hollywood, and as the host of The Hazel Scott Show, the first television show to feature an African American woman as a recurring host.

Throughout her career, Scott used her platform to advocate for civil rights and Black social advancement. She regularly criticized racist legislature and attitudes in the United States, going so far as to refuse to play at segregated venues. Scott won a 1949 lawsuit against a restaurant in Pasco, Washington that refused to serve her, lighting a fire that led to increased momentum in movements against discrimination in the state.

Scott’s presence as a Black celebrity activist laid the groundwork for the later generations. Today, it isn’t at all uncommon to see

a Black celebrity using their platform to speak out against injustice. Actors, athletes, comedians, talk show hosts, and others take to social media or to the streets to protest racial discrimination and scores of other humanitarian concerns. Without fearless and unapologetic superstars like Scott, there’s no telling how many outspoken voices we’ve come to know and love would have lacked the courage to speak up.