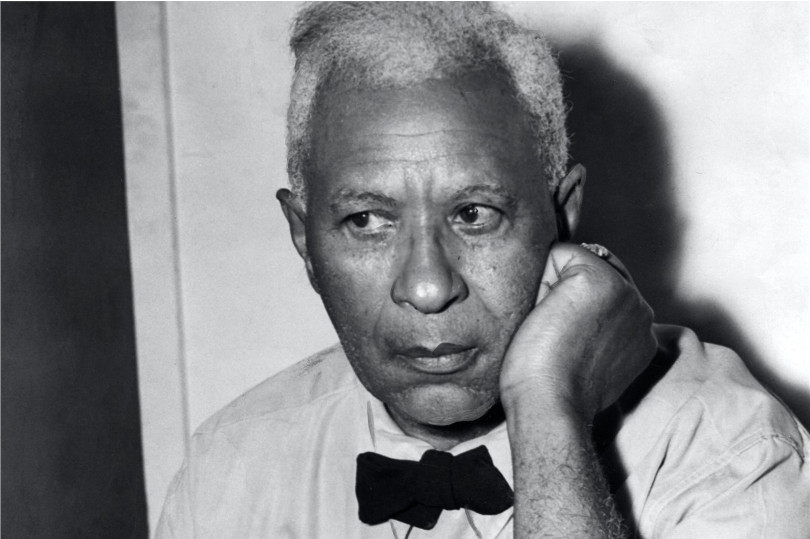

Garrett Augustus Morgan Sr., born on March 4, 1877 in Claysville, Kentucky, is a name that comes up often during each Black History Month. The inventor, businessman, activist, and self-proclaimed “Black Edison†is best remembered today as the inventor of an early version of the three-way traffic light. He was a member of the burgeoning NAACP and helped found Cleveland, Ohio’s longest-running and most iconic black newspaper, the Call and Post. Morgan’s professional and financial success in the racially volatile early twentieth century serves as an inspiration to us all, and especially to black Americans during Black History Month.

Morgan’s traffic light is often used as an example of the indispensability of African American history and culture, for where would we be without so crucial an innovation? The ever-impactful work of Black trailblazers like Morgan, George Washington Carver, Benjamin Banneker, and Lewis Howard Latimer prove that Black history is not only inextricable from American history but also from world history. Black industry and creativity have contributed greatly to the history of all industry and creativity, despite the many historical revisionists who would have you believe otherwise.

A lesser-known fact about Morgan—and one that carries considerable irony—is that, along with the traffic light, he also invented the first chemical hair relaxer. In 1909, fourteen years before his most famous invention, he developed a straightening cream that he would later sell through his own G. A. Morgan Hair Refining Company. The act of hair straightening among African Americans, while popular since its invention, is sometimes seen as controversial. Critics of the practice see it as an attempt at assimilation into white society, an act that one wouldn’t typically expect from such an inspirational figure of Black history.

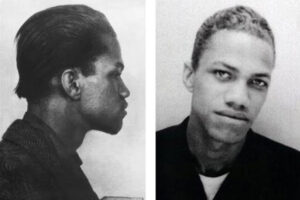

A young Malcolm X sporting the “conk” hairstyle, which was achieved through the use of chemical relaxer.

The more militant of us might disagree, but I don’t believe Morgan’s hair care breakthrough constitutes any form of racial treason. I don’t see him as a sellout. An opportunist, absolutely—it’s true that he likely sought to capitalize on twentieth-century Black America’s desire for social elevation and acceptance. But at a time when an unwavering allegiance to one’s authentic Black self could mean harassment, bodily harm, or even death (and indeed it still can), I see this desire as taking a different, less traitorous hue. Even Malcolm X, before denouncing it, wore straight hair when he was Malcolm Little.

The ironic tension between Morgan’s impact and his contentious invention reveals that there is no one way to uplift oneself and one’s community. For example, the midcentury “Black is beautiful†and Black Power movements heavily emphasized reconnection with cultural roots, such as the preference for one’s natural hair. While this idea remains widely accepted and has heavily influenced the proliferation of natural Black hairstyling, hair straightening is still very prevalent in the Black community. Morgan, the NAACP member, HBCU donor, and black country club founder, was not a sellout for inventing a relaxer, just as relaxer users, then as now, are no less Black than their natural counterparts. Belittling another’s Blackness in this manner sidelines unity in favor of arbitrary division. What could be “less Black†than this?

Featured image of Garrett Morgan courtesy of Cleveland News. Article image of Malcolm X courtesy of arogundade.com.