The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) is home to one of the largest collections of items in the Smithsonian network. With nearly eight hundred fifty thousand items to its name, there’s hardly a corner or corridor lacking something to show. Even its loneliest nooks — a path leading only to a small seating area, a wall adjacent to the first-floor restrooms — are rife with display cases featuring pottery, glasswork, textiles, toys, tools, masks, and countless other categories of Native production.

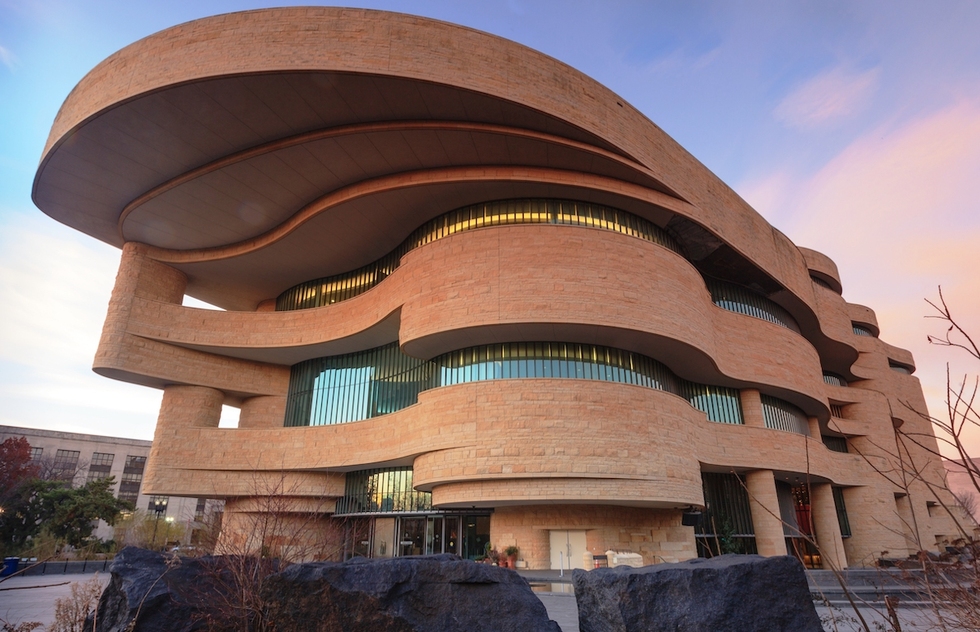

Despite the collection’s volume, the museum itself is deceptively small from both the outside and inside. Externally, the expressionist building, designed by Indigenous Canadian architect Douglas Cardinal, is dwarfed by several of the Smithsonian museums on the National Mall. The National Museum of African American History and Culture, for example, boasts an extra two hundred thousand square feet despite containing only one-twentieth of the NMAI’s number of items. Internally, the collection is so widely distributed that the small picture — display cases, rooms, exhibitions, floors — hardly seems capable of adding up to the big picture. Visitors aware of the collection’s size might be surprised to find that only two of the museum’s four floors house more than one exhibition unless you count the second floor’s small series of informational displays on Native presence in the Chesapeake Bay region as one. In addition to its unique and unconventional use of space, the secret of the NMAI’s composition is that each of its exhibitions runs as deep as the history it unfolds.

The fourth but chronologically first floor contains the exhibitions “Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations” and “Our Universes: Traditional Knowledge Shapes Our World.” Between the two exhibitions lies the circular, one-hundred-twenty-seat Lelawi theater, in which visitors watch “Who We Are,” a thirteen-minute orientation film depicting the range of contemporary Native communities and cultures while casting images on screens and across the dome ceiling.

“Nation to Nation,” one of the larger exhibitions in the museum, chronicles the history of diplomacy between American Indians and the United States with a focus on the prevalence and impact of treatymaking. The exhibition tracks the movement of these relations from the symbiotic ethics of the Two Row Wampum Treaty, a seventeenth-century agreement between Dutch traders and Iroquois officials, to the more parasitic and hawkish treaties devised by colonists simply to coerce Native people into giving up their land. The dichotomy between colonial and Native perceptions of certain treaties and broader concepts like land and leadership is articulated on many informational displays throughout the exhibition, each one juxtaposing the opinions of the “United States” or “European Nations” and the “Native Nations” or specific groups within those nations. “Nation to Nation” also contains some of the NMAI collection’s most impressive holdings, from centuries-old weapons, tools, and garments to a scheduled rotation of eight original treaties being loaned from the National Archives and Records Administration.

“Our Universes,” a celebration of Native cultural philosophy, turns back the clock much further than the colonial period to give visitors insight into different groups of American Indians’ ways of thought and life. I say “much further” because, as it happens, there’s not much that’s older than creation itself. The exhibition sprawls with videos, recordings, and materials pertaining to the beliefs and practices of eight Indigenous communities throughout the Americas, and is thematically centered on each of the communities’ unique reason for being. Central to the theme is the power of the creation story, being that the values, symbolism, and mythos of each community’s story are invaluable to everything they are today.

The third floor further establishes the importance of the creation story with “Preston Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight,” a yearlong exhibition featuring the glasswork of the titular artist. Until January 29 of next year, visitors are able to follow renowned Tlingit

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ca/33/ca33dfa5-b5b4-4638-80fa-d718284bf96a/preston_singletary_011.jpg)

American glass artist Preston Singletary into a world before time, a time before the world. Singletary’s sculptures tell the Tlingit creation story of Raven, creator of everything, in striking artistic detail. The experience of Singletary’s storytelling consists not only of his glasswork, but also the careful curation of music, noises, lighting, and room arrangement, resulting in an exhibition as immersive as it is informative.

“Raven and the Box of Daylight” shares the third floor with “Americans,” a terrifically large exhibition with some of the museum’s most eye-catching pieces. “Americans” showcases the many ways in which American Indian images and stories influenced and continue to influence American identity. Its main walkway takes visitors through an expansive showroom of memorabilia inspired by American Indian imagery. Visitors are met with a vintage bright yellow Indian Chief motorcycle upon entry, and with a few steps are wholly surrounded by decades of Native-themed consumer products, advertisements, and television clips. A Tomahawk cruise missile, a Florida State Seminoles onesie, a Chicago Blackhawks jersey, and packs of Natural American Spirit cigarettes are but a few of the items lining the walls. Accessible from this room are rooms dedicated to informing visitors about the cultural impact of the Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears, Pocahontas, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn, all of which are densely packed with artifacts and reading material.

The final full exhibition is the second floor’s “Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces,” a relatively small collection of items and personal narratives related to the history of Native involvement in the United States military, a history dating back to the Revolutionary War. On the same floor is the previously mentioned “compact exhibition” entitled “Return to a Native Place: Algonquian Peoples of the Chesapeake.” Unconfined by a room, the displays inform their readers of the past and present of Native presence in their own area: the Chesapeake Bay region.

While the method employed by “Return to a Native Place” is a bit on the nose, through no fault of its own, every exhibition in the museum allows its viewers to return to a native place. More accurately, it allows them to recognize that they’re already in one, and that their and the nation’s history is being constantly influenced by it. American visitors less knowledgeable of Indigenous history won’t just leave the NMAI knowing more about the broad constellation of American Indian history and culture — they’ll leave knowing more about themselves. That’s more than most museums can say.