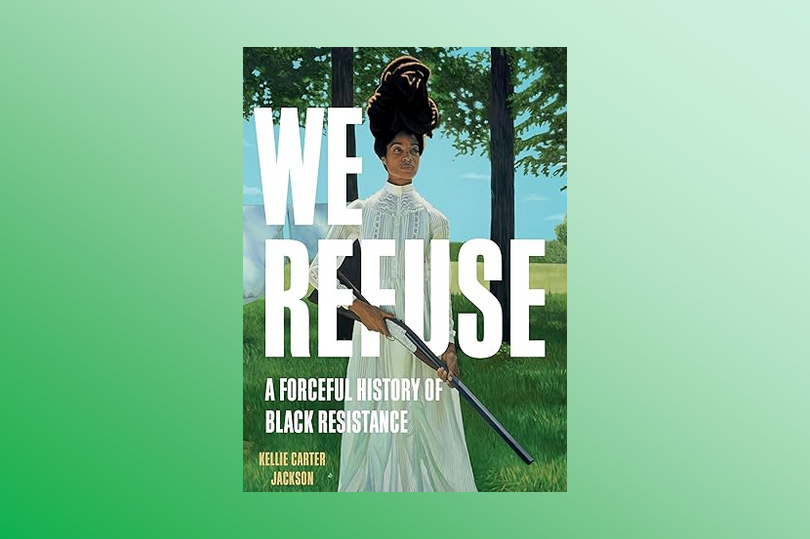

We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance, by Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson is one of the most compelling narratives of the Black experience I have read. The fact that she relays it from the perspectives of strong, defiant Black women is even more compelling. Black resistance typically conjures up visions of Denmark Vasey, Nat Turner, Toussaint Louverture, The Black Panther Party, or maybe Malcolm X. It rarely, if ever, leans into the stories of the gun toting, defiant, strong Black women and the roles they’ve played throughout our history. The cover of We Refuse immediately grabs your attention as a Black woman stands alone comfortably brandishing what appears to be a Winchester double-barreled shotgun. It just gets better from there.

It’s easy to get caught up in our historical stereotypes of the Black experience and focus on only a handful of narratives. But like many, those narratives begin to get stale and worn and even frustrating as we continue to see rampant bigotry, racism, sexism, classism, and a host of other ‘isms play out. Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson offers a different view of the Black journey. One of defiance, courage, and resistance with names that have rarely been heard and definitely don’t make it to mainstream history books; Black or white. She weaves a compelling journey through 5 amazing chapters: Revolution, Protection, Force, Flight, and Joy. Each chapter stands alone in the phases we find ourselves in over time, yet they also build on each other along the way. Each chapter highlights scores of strong Black women that deservedly need their stories to be told to our sons, daughters, and grandchildren – especially our girls.

To get a feel for the author, please watch our interview Live with Branson Brooks: Featuring Dr Kellie Carter Jackson on You Tube. Not only will you see the passion of the writer shine through, but her fire and determination to not sit quietly by will move you. Also, Dr. Jackson being a Howard University alum is another reason to support her book! It’s impossible to do justice to the book in a few short paragraphs, so take the next few words as nothing more than a preview of a tremendous read.

In Chapter 1: Revolution, Dr. Jackson recounts the story of how the bone marrow transplant that cured her brother of sickle cell anemia was revolutionary for him and her family as it “changed the trajectory” of their lives. She uses this story to highlight the fact that revolutions do not require bloodshed, but they do require sacrifice. The sacrifice in this case was the donated bone marrow provided by her sister to cure their brother. The key takeaway in this chapter for me is “Revolutions do not ask for consent. They demand cooperation.” Although this sounds very cooperative and passive, the rest of the chapter highlights episodes in American history where Blacks have fought to change the trajectory of racism, classism, and mass incarceration.

Chapter 2: Protection outlines the collection of activities Blacks have to employ to confront oppression. It can range from legal to physical to even violence in order to match the level of the offense. This chapter draws upon the role of Black vigilante groups that protected neighborhoods from white violence. Here, Dr. Jackson tells the story of Lucy Stanton (October 16, 1831 – February 18, 1910), the first African American woman to complete a four-year course of a study at a college or university from Oberlin Collegiate Institute (now Oberlin College) in 1850. Stanton’s commencement address “A Plea for the Oppressed” represents the protections required for Black people during antebellum slavery.

Chapter 3: Force is my favorite chapter. Maybe it’s because it epitomizes the cover. It might also be because it brings to mind an aunt who was known to carry a loaded .45 – or my grandmother who had a .38 caliber revolver. That’s where this chapter begins as Dr. Jackson recalls finding that her grandmother kept a small caliber pistol in her nightstand. This chapter “illustrates the powerful relationship between Black women and force in the face of anti-Black violence.” The author defines force as the energy needed to influence or change a system. Here is where we learn about the gun-wielding Black heroine Carrie Johnson (17) who defended herself and her father during the D.C. Race War of 1919.

Chapter 4: Flight refers to the exodus of Blacks to the north from slave holders – the great migration of 1890-1970 where 6-8 million Black southerners moved north and west to flee white racism. Dr. Jackson uses the stories of novelist Jamaica Kincaid about the difference between being a tourist and a native, as it refers to being Black. Being Black or native creates a sense of being “stuck” in a place where circumstances prevent or hamper the ability to leave. This chapter even speaks to the flight of enslaved Blacks to fight for the British during the Revolutionary War, and Ona Judge, who escaped from Martha Washington in May 1796.

We Refuse concludes with Chapter 5: Joy. This chapter recalls the eulogy of one of her sisters where her brother contrasts happiness and joy; how “happiness is fleeting but joy is grounded by grief and birthed from hard places.” I can’t begin to do this chapter justice as Dr. Jackson speaks to the compounding grief and hardships that Black people face in America. Her comment that “white people get to be happy while Black people get to have joy” sums up the chapter. We have indeed emerged from hard places.